29 September 2023

There’s no such thing as a risk-free investment!

19 June 2023

ECB, FED: 8 questions to understand their role in the economy

Essential to the monetary balance as well as to the financial stability,…

11 May 2023

DCA or the smart art of buying gold

The health crisis of the last two years and the current geopolitical turmoil…

21 February 2023

Could inflation be both the problem and the solution?

Rising prices are undoubtedly the indicator that speaks loudest to the most…

22 March 2022

Bank run: Do we need to worry about a wave of banking panic?

At the moment, there is a new wave that is not talked about as often : the…

27 January 2022

How can we diversify savings at times of crisis?

1 October 2020

FinCEN Files: A swirl of revelations about banks and money laundering

FinCEN Files, the scandal making banks tremble. VeraCash reviews the abuses in…

7 August 2019

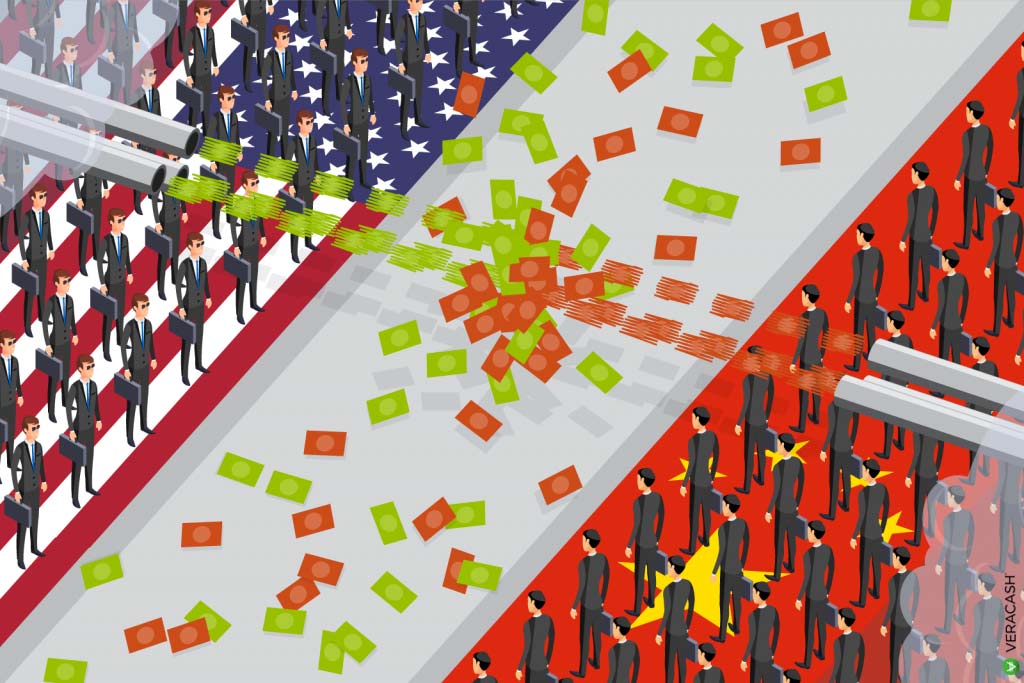

How can we prepare for the currency war?

Once you realize that the States can wage war against one another by means of…

23 July 2019

Who creates money?

What is fiat money? What is bank money? What is money creation? Find all the…

- 1

- 2